The Making of The Great Escape Documentary

Director John Sturges and his crew arrived at Geiselgasteig Studios in

rural Bavaria in April 1962. Art director Fernando Carrere immediately began

designing the tunnel sets on the studio's sound stages. They were

constructed of wood and skins filled with plaster and dirt and open on one

side with a dolly track running the length of the set in order to shoot

scenes of prisoners scooting along through them.

The barracks interiors for The Great Escape were also constructed on

sound stages at the German studio.

The Making of The Great Escape PART 1

Jud Taylor, who played Goff, the third American in the prison, said the camp set was so authentic and impressive that one day he came upon a man walking his dog who was very distressed when he came upon the site. The man was greatly relieved, Goff said, when he learned it was just a movie set.

The Making of The Great Escape PART 2

The filming of The Great Escape began in June 1962 but because of heavy rains, the schedule was changed to shoot interiors from the middle portion of the picture first.

Early on in the production, Sturges began receiving memos from distributor United Artists requesting female roles in the picture. One even suggested having the dying Ashley-Pitt (played by David McCallum in the film) cradled in the lap of a beautiful girl in a low-cut blouse. The studio wanted to cast this bit by having a Miss Prison Camp contest in Munich. Sturges would have none of it.

The Making of The Great Escape PART 3

According to Sturges, The Great Escape screenplay went through six writers and eleven versions, and was still a work in progress during the actual shooting. "I'm not proposing that's a good way to make a picture, but it was the right way to make this one," he later said.

The Making of The Great Escape PART 4

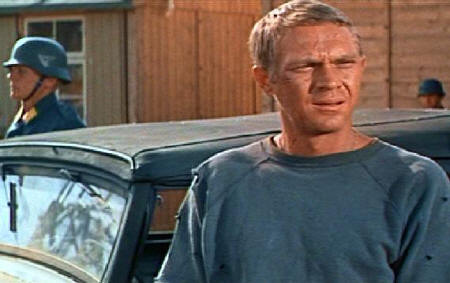

"McQueen was an impossible bastard," Burnett said. "Oh, he drove you crazy."

McQueen reportedly rarely mingled with others away from the set, preferring to stay in the chalet he rented for himself and his family and travelling to the set each day in a chauffeur-driven limousine.

"[James Garner] is a bright and likable, uncomplicated, and talented guy. He's an awfully good actor and I admire him as a person," Sturges was quoted in Garner's biography by Raymond Strait (St. Martin's Press, 1985). "McQueen and Garner got on quite well because they had so many common interests. Both were interested in cars and racing and that sort of thing."

Co-star James Coburn later commented on John Sturges's direction: "He had great faith in the actor. He would storyboard everything. He never talked to me about character or about anything. What was in the script was what was shot; what was on the storyboard was the way it was shot."

Jud Taylor said that Sturges "gave you [as an actor] a great deal of freedom to try things, but he had a very clear sense of when he liked something."

James Garner also brought earlier military experiences to bear for his role. During the Korean War, he was a "scrounger" for an entire company, much like his character in the picture, "so I knew a little bit about the hustle...and I knew basically what Hendley would be like."

Wally Floody, who was the real-life "Tunnel King" on whom Charles Bronson's character was based, was hired as technical adviser. His tasks (such as exploring the tunnel sets to determine if they were accurate in size) kept him busy as much as twelve hours a day. Floody told Sturges's assistant (and uncredited stunt pilot) Robert Relyea that he knew the production was on the right track and close to reality when he began to get nightmares about his prison camp experiences.

David McCallum said that when anyone, cast or crew, was sitting around the camp set with time on their hands, they were handed a length of rubber string around which they wrapped other pieces of rubber at six-inch intervals to create the hundreds of yards of "barbed wire" needed to surround the prison. The entire fence, McCallum said, was made by the company in its spare time.

After two months shooting in the camp, the production moved to the town of Fussen near the Austrian border for post-escape scenes. Because he was already running out of money, Sturges decided to cut back on his original plan to film in a number of locations. Fussen had all the elements he needed to simulate the various places where the escapees run, including nearby meadowlands to shoot McQueen's required motorcycle sequence.

Although McQueen was an expert motorcyclist, the major stunt of jumping the barbed wire fence was considered too risky by the studio for a star of his calibre, so a friend of his, Bud Ekins, was hired to perform the shot. Before leaving for Germany, Ekins bought two Triumph motorcycles and converted them to look like authentic German bikes of the period.

Ekins's scene was one of the last shot during principal photography on The Great Escape.

Ekins did the jump scene, but McQueen did all the rest, including playing his own German pursuers when it turned out the hired German stunt riders couldn't keep up with him. The scene would be shot first with McQueen fleeing the Nazis on his bike. Then he would change costume and shoot again as a pursuer with his face obscured.

The German National Railroad Bureau co-operated with Sturges' production to provide trains and logistics for the railway escape sequences. Platforms were fitted on passenger cars to accommodate huge arc lamps to illuminate the train interiors. On one flat car, a large Chapman crane was set up to swing out over the passenger car and film the jump from the moving train performed by two stuntmen disguised as Garner's and Pleasence's characters. The bureau attached a special radio operator to the crew to alert the train engineer to any potential traffic on the main line. The shooting schedule was squeezed in between actual runs on the rails. The bureau gave the production certain times and lengths of tracks to work on until a passenger train was scheduled to come by; the film train then had to duck onto a siding until the other passed.

During the jump sequence, the crew was warned at the last possible second that the crane was about to slam into a pole. It was withdrawn in the nick of time.

Sturges's assistant Robert Relyea was an amateur pilot and offered to fly the plane himself for the sequence in which Garner and Pleasence commandeer a plane for their escape. In one segment he had to simulate the plane losing power and descending over a line of trees. According to Relyea, a farmer in his field saw the plane with its Nazi insignia coming in low over his head and threw his rake at it. Another time Relyea was arrested when he had to put the plane down in a field that happened to belong to a German aviation official. He also piloted the plane in the crash shot, knocking himself unconscious and being taken to the hospital where he woke up later feeling a sharp pain down his back.